Diabetes – from death sentence to treatable disease.

The first descriptions of diabetes mellitus, commonly known as the “sugar disease”, is found in ancient records. Up until a hundred years ago, however, there was no effective treatment for those affected, which is why diabetes quickly led to death. Only the discovery of insulin eased the horror of the disease. Since then, pharmaceutical research has produced various improvements that have greatly boosted the quality of life of diabetes patients.

The long road to breakthrough

Although academics were already describing a symptom of “honey-sweet urine” several centuries before Christ, a milestone was not achieved until the mid-19th century, when physicians identified the key role of the pancreas. In the following decades, new discoveries followed in quick succession. In 1916, it became possible to isolate insulin from the tissue of an animal pancreas for the first time. Modern diabetes treatment was born six years later: The process was patented following the first successful treatment, and companies in North America and Europe began producing insulin.1

The further development of insulin therapies

The decades that followed were also shaped by innovation. Between the 1930s and 1950s, medications that enabled delayed insulin delivery were introduced to the market, allowing the number of daily injections to be reduced. In addition, since the 1970s, insulin has been administered to patients in a chromatographically purified form, which has increased tolerability. Since the 1980s, the active ingredient can be produced biotechnologically, which is why no animal-based insulins have been on the market in Switzerland since 2015. This led to a further reduction in incompatibility. To better control insulin therapy, so-called insulin analogues have been developed that better reflect the action curve of insulin produced in the pancreas. Treatment for type 1 patients usually consists of a long-acting basal insulin for primary needs and a short-acting insulin that can be administered as required (e.g. with meals or to correct excessively high blood glucose levels). A wide range of short-, medium- and long-acting insulins are now available.1

Greater quality of life thanks to modern medical products

Not only insulin, but also the associated medical products were further developed during the 20th century. Syringes for self-injection became available just two years after the first successful treatment of a diabetic patient. Insulin pens have been available since the 1980s, replacing syringes and allowing those affected to administer the substance more flexibly, for example when traveling. The first insulin pumps were also developed. These are particularly suitable for type 1 diabetics. The pumps are now not only much smaller, but also have a higher dosage accuracy.

Determining blood sugar levels has also become much easier over time. In addition to blood glucose monitors, various sensors are now available that are attached to the skin and continuously measure blood glucose levels. Furthermore, systems are now available that combine insulin pumps and sensors with electronic controls (e.g. via an app) and act as a kind of “artificial pancreas”. These innovations reduce fluctuations in blood sugar levels, which makes life much easier for patients.2

Stepwise treatment for type 2 diabetes: Alternatives to insulin

In the 1960s, it was found that there are different types of diabetes mellitus. In type 1 diabetes, as described above, the body can no longer produce any insulin – those affected are dependent on insulin treatment.

In the case of type 2 diabetes, however, the body simply does not respond strongly enough to the insulin it produces. Within the framework of what is called “stepwise treatment”, various active substances are now available as treatment options for this form of the disease.

The primary treatment for type 2 diabetes is a lifestyle change consisting of a modified diet and an increase in physical activity. If blood sugar levels do not drop despite these measures, oral antidiabetic agents are used. Metformin, which has been approved in Switzerland since 1960 and increases the sensitivity of the body’s own cells to insulin, is often used as the first-line treatment. The treatment can be supplemented with other medications in a second or third step. The treatment is selected according to the individual requirements of the patient. In addition, sulfonylureas, which stimulate insulin release in the pancreas, have also been used for decades.

If cardiovascular risk factors are present, “SGLT-2 inhibitors” or “GLP-1 receptor antagonists” are now used. SGLT-2 inhibitors promote sugar excretion via the kidneys, while GLP-1 receptor antagonists (glutide) inhibit the release of an insulin antagonist and control meal-related insulin release. These have also been approved in pill form in Switzerland since 2020. before that, they had to be administered using syringes.

Another group of active substances that can be used in the second or third step are the DPP-4 inhibitors (gliptins). These act similarly to the GLP-1 receptor antagonists, but do not show the risk-reducing effects on comorbidities. Glinide (similar effect to sulfonylureas) and glitazones (increase insulin sensitivity of the muscle cells) can also be administered as part of the stepwise treatment, but are less common today than the active substances described above.

Insulin is only used in the third or fourth step if treatment with oral antidiabetic agents alone is not successful. Depending on the patient with type 2 diabetes, it is determined individually whether a short-acting or long-acting insulin is suitable and whether administration should continue in combination with oral antidiabetic agents.3, 4

Since the described medications can be administered orally instead of by injection, taking them requires less effort by the patient. In many cases, it is not even necessary to treat type 2 diabetes with insulin, since the disease can be controlled well with oral antidiabetic agents. Furthermore, during insulin therapy, the sugar is stored in the body as fat deposits, which can lead to weight gain. However, increasing body weight is particularly problematic for patients who are already struggling with excess weight. Oral antidiabetic agents, on the other hand, sometimes even have the opposite effect and can lead to weight loss. The aim of treatment for type 2 diabetes is to push back the disease to a milder stage and – where necessary – to reduce body weight. In many cases, this means that insulin therapy can be avoided.5

The goal of modern diabetes treatment

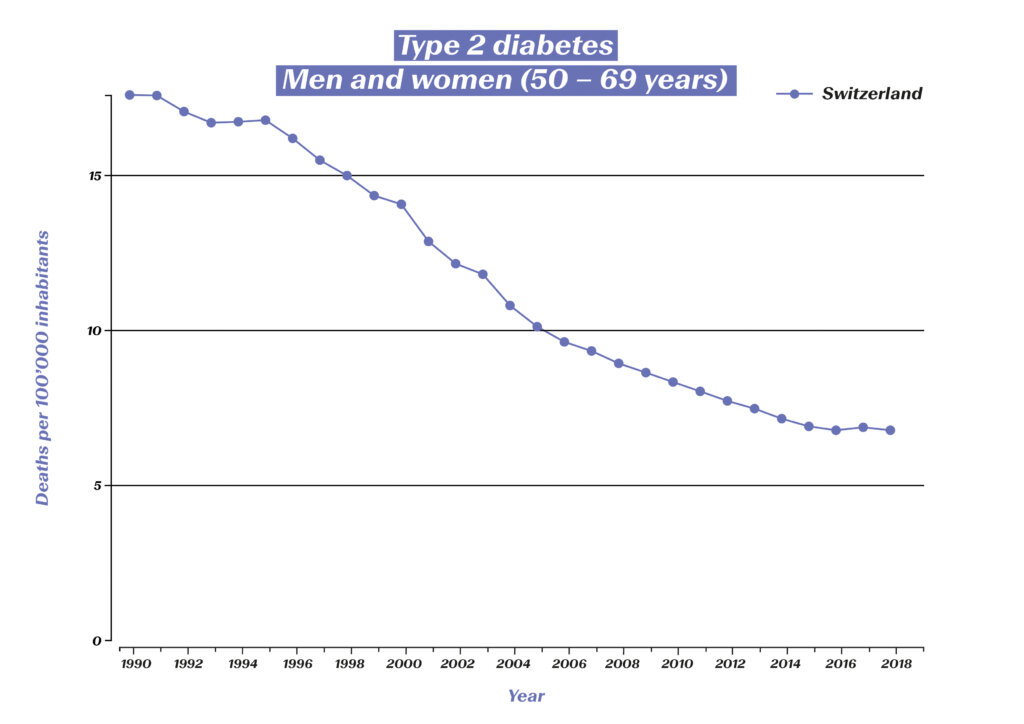

While diabetes still meant a death sentence in most cases at the beginning of the last century, those affected are now able to lead a practically normal life with appropriate treatment. A number of studies show a significant increase in life expectancy for people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. For the periods of 1990–1999 and 2000–2016, a decrease in the mortality rate of people affected by diabetes was observed in 75% of all European countries.6 In Switzerland, too, mortality from diabetes mellitus has been declining since 1990:

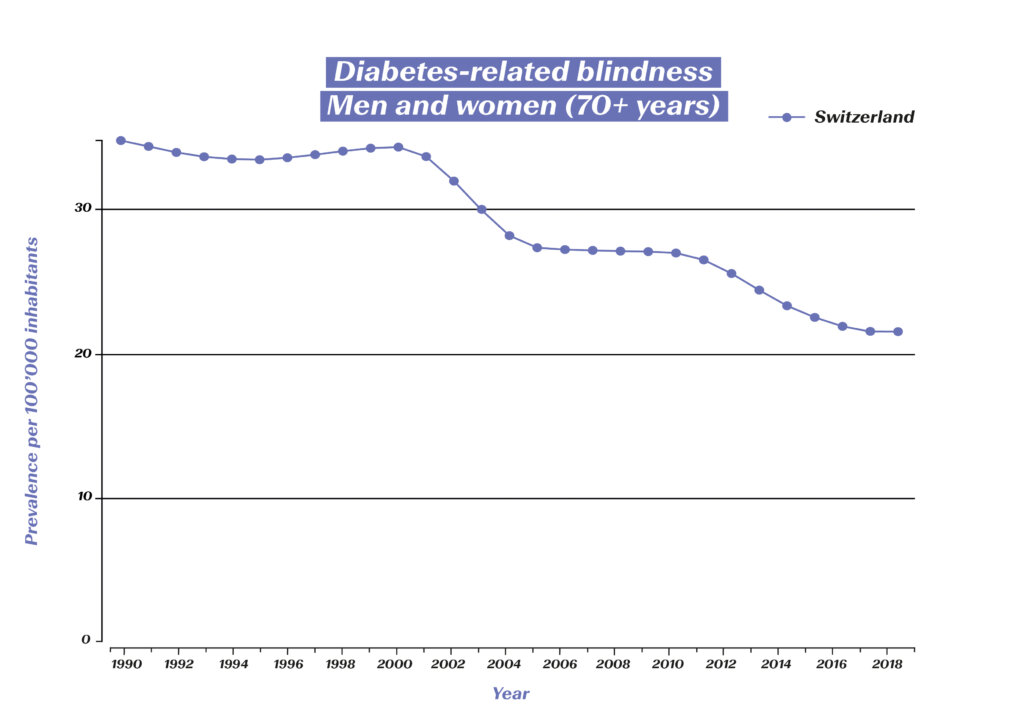

However, the aim of modern diabetes treatment is no longer just the survival of those affected, but also the prevention of consequential diseases (e.g. diabetic retinopathy, diabetic foot syndrome and the associated amputations, kidney failure) and the optimization of quality of life. There are also figures to show how well this is now being achieved: The incidence of amputations in diabetes patients has fallen significantly. Figures from eleven OECD countries show a decline of almost 30% between 2000 and 2013.7 The blindness rate has also been massively reduced in the past 30 years:

Diabetes-related blindness among 50–69-year-olds in Switzerland (source: Global Burden of Disease (GBD)), https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/#

Diabetes-related blindness among 70+-year-olds in Switzerland (source: Global Burden of Disease (GBD)), https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/#

It is foreseeable that research will continue to generate further innovations in the coming years that will give people with diabetes even greater flexibility. What is known as “precision medicine” will play a key role here. Thanks in part to artificial intelligence methods, it is already becoming increasingly possible to identify and treat subtypes of diabetes as well as the associated risks and complications.

1 Österreichisches Diabetes-Museum: Die Geschichte der (modernen) Diabetes-Behandlung. https://diabetes-museum.at/geschichte-diabetesbehandlung

2 Deutsche Diabetes-Hilfe (2022): 100 Jahre Insulin: Die Geschichte des lebenswichtigen Hormons. diabetesde.org/100-jahre-insulin-geschichte-lebenswichtigen-hormons

3 Mehnert, Hellmut (2019): Orale Antidiabetika: Ab wann? Welche? Wie lange? Ars Medici 21: 721-723.

4 Universitätsspital Zürich (2022): Diabetes mellitus – Behandlung. https://www.usz.ch/fachbereich/endokrinologie/angebot/diabetes-mellitus/#typ-2-diabetes

5 Diabinfo (2021): Diabetes Typ 2: Medikamente. https://www.diabinfo.de/leben/typ-2-diabetes/behandlung/medikamente.html

6 Kulzer, B. (2022): Körperliche und psychische Folgeerkrankungen bei Diabetes mellitus. Bundesgesundheitsblatt 2022 (65): 503–510.

7 Carinci et al. (2020): An in‑depth assessment of diabetes‑related lower extremity amputation rates 2000–2013 delivered by twenty‑one countries for the data collection 2015 of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Acta Diabetologica 57(3): 347-357.

Diabetes mellitus

Since the body can no longer produce the metabolic hormone insulin (or at least not in sufficient quantities), those affected suffer from elevated blood sugar levels.

Type 1 diabetes, which often begins in adolescence, is an autoimmune disease that destroys the body’s insulin-producing cells. As a result, the body can no longer produce insulin.

In the case of type 2 diabetes (“adult-onset diabetes”), on the other hand, the body does not respond strongly enough to its own insulin. Common causes of this are obesity and an unhealthy diet.

In Switzerland, almost half a million people suffer from diabetes. Approximately 40,000 of these people are affected by type 1 diabetes. With appropriate treatment and adherence to the prescribed regimen, both type 1 and type 2 patients can now achieve a normal life expectancy.