The symptoms of hepatitis were first described as early as the 5th century BCE. However, nobody knew where hepatitis came from or how to treat it at that time. Today effective vaccinations offer protection against hepatitis A and B. Although there is still no vaccination against hepatitis C, the chances of recovery are over 95% thanks to modern treatments.1

Unidentified for centuries

Reports of outbreaks of epidemic jaundice, a common consequence of hepatitis, date back to ancient times. However, it was not until the mid-20th century that it was discovered that hepatitis is mostly caused by viruses. In 1947, the British physician F.O. McCallum first made the distinction between hepatitis viruses A and B. In the late 1980s, researchers finally discovered the hepatitis C virus, which is often chronic and therefore considered the most dangerous hepatitis virus. An estimated 400 million people worldwide are infected with one of the virus variants, and over 1.3 million people die from the disease every year.2

Hepatitis can be treacherous because many symptoms occur gradually. It can often take years before those affected notice that they have been infected – with serious consequences for the liver.

Breakthrough vaccination against hepatitis

hepatitis A and B (also available as combination vaccine). The first hepatitis A vaccines were approved in Europe in 1991. They are now on the World Health Organization (WHO) List of Essential Medicines, as they offer protection against one of the most common infectious diseases in high-risk regions such as Africa, Asia, Central America and South America with an effectiveness rate of 95–99%. Vaccination is therefore recommended for all travelers visiting a country with a high prevalence of hepatitis A.3

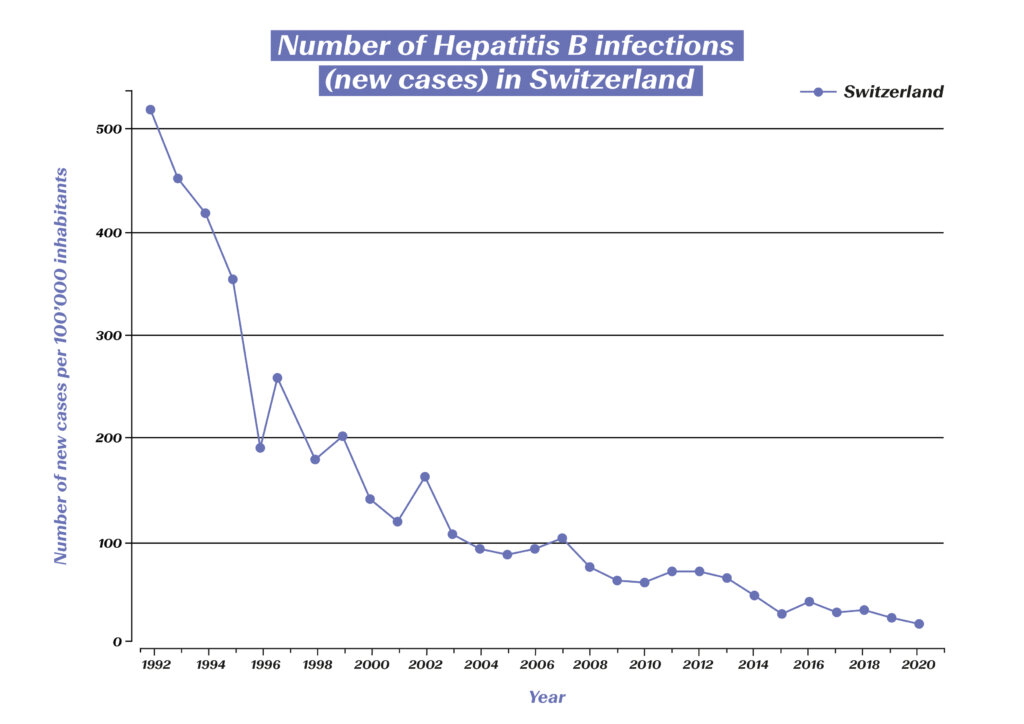

Vaccination against the hepatitis B virus has been available since 1984. It is one of the primary vaccines in Switzerland and offers vaccinated people 10 years of immunity – with a booster in adulthood, this immunity even lasts for decades.4 The vaccination recommendation for adolescents, which the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) introduced in Switzerland in 1998,5 has significantly contributed to the steady decline in the number of new hepatitis B infections in Switzerland:

Number of hepatitis B infections (new cases) in Switzerland. (Source: Statista) https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/544724/umfrage/neuerkrankungen-an-hepatitis-b-in-der-schweiz/

Thanks to the high rate of immunization, the estimated global prevalence in children under the age of five has been reduced from 4.7% to below 1% over the past 40 years. Studies also show a threefold lower incidence of liver cancer caused by this virus variant among vaccinated people. The hepatitis B vaccine could therefore even be described as a vaccination against cancer.4

Advances in treatment thanks to targeted research

If infection with a hepatitis virus occurs and becomes chronic, this can have serious consequences and may lead to liver cirrhosis or liver cancer. While hepatitis A never becomes chronic, this can happen with both hepatitis B and C. Thanks to new developments in medical research, however, chronic disease can now be treated effectively.

In the event of a hepatitis B infection, antiviral agents are used which reduce the viral load in the blood, thereby preventing serious complications. In addition, new virological diagnostic methods are making it increasingly easy to determine the best treatment option.

Treatment of hepatitis C has come a long way since the virus was discovered in 1989. At first, patients were treated with interferons for six to 12 months. The cure rate was initially less than 20%, and involved considerable side effects for the patients. In the second decade, the cure rate was gradually increased to 45%, in part through the combination with ribavirin. Decisive progress has finally been made in the last two decades – the identification of the protein structure enabled the development of highly potent antiviral drugs with an excellent safety profile. In 2015, a breakthrough in cure rates and side effects was finally achieved with interferon-free treatment.6 Until recently, chronic hepatitis C was the most common cause of liver transplantation in Switzerland, but now 98% of all infections can be cured. On average, affected individuals are now virus free after just 8–12 weeks of treatment. As of 2022, all medications for the treatment of hepatitis C can be prescribed by doctors without restrictions.7 The treatments that have emerged through the power of biomedical research are now presenting a prospect long thought impossible: the global eradication of hepatitis C and thus of millions of human lives saved.

The WHO has therefore set itself the goal of global hepatitis B and C containment by 2030. The plan is to achieve this through a combination of different measures, but vaccines are the key to success. It can be expected that the rapid progress made in the development of COVID-19 vaccines will also boost the development of a vaccine against hepatitis C.8 Also, intensive research continues into even more effective treatment options for hepatitis B. In addition, the development of diagnostics continues to play a key role in the global fight against hepatitis.

1 Deutsches Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (2019): Hepatitis – Eine unterschätzte Krankheit. https://www.gesundheitsforschung-bmbf.de/de/hepatitis-eine-unterschatzte-krankheit-mit-hoher-dunkelziffer-9689.php

2 Hepatitis Schweiz (2022): Was ist Hepatitis? https://hepatitis-schweiz.ch/formen/was-ist-hepatitis

3 Robert Koch Institut (2019): Hepatitis A. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Merkblaetter/Ratgeber_HepatitisA.html

4 Gerlich, Wolfram H. (2022): Hepatitis-B-Impfstoffe – Geschichte, Erfolge, Herausforderungen und Perspektiven. Bundesgesundheitsblatt 65: 170–182.

5 Bundesamt für Gesundheit (2020): Impfungen – Zahlen und Fakten. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/nationale-strategie-impfungen-nsi/zahlen-fakten.html#:~:text=Schweizweit%20sind%2070%20Prozent%20der,von%2012%20bis%2089%20Prozent

6 Grätzel, Philipp (2019): Die Interferontherapie ist Geschichte. 13th Expert Summit on Viral Hepatitis, 10./11. Februar 2017, Berlin (Veranstalter: MSD). https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s15006-017-9415-x.pdf?pdf=button

7 Hepatitis Schweiz (2022): Neu können Hepatitis-C-Medikamente auch von Hausärzt:innen verschrieben werden. https://hepatitis-schweiz.ch/news/neu-koennen-hepatitis-c-medikamente-auch-von-hausaerztinnen-verschrieben-werden

8 Swiss Medical Forum (2022): Hepatitis C ist heilbar: eine Erfolgsgeschichte der biomedizinischen Forschung. https://medicalforum.ch/de/detail/doi/smf.2022.09003

Early diagnosis and prompt, appropriate treatment are the key to successfully dealing with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The widespread inflammatory joint disease has been around for thousands of years – but breakthroughs were only made in the 20th century. The disease can now be managed so well in more and more affected individuals that they can live with almost no symptoms.

Millennia-old bone finds and famous patients – the history of RA

Bone finds have shown that rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was around as early as 4500 BC. From then on, texts often mention diseases with symptoms matching those of RA. A famous patient in the 17th century was the Flemish painter Rubens, who often depicted hands with rheumatism in his later works. In 1859, the British doctor Alfred Baring Garrod introduced the term “rheumatoid arthritis” for the first time. At that time, treatments were limited to home remedies such as leech therapy. Medicines containing opiates and alcohol were later given to patients to provide some relief.

In the early 20th century, advances in radiology allowed RA to be more accurately diagnosed and differentiated from related conditions such as osteoarthritis. This marked the beginning of the era of modern approaches to RA – in 1941, the American Rheumatism Association recognized RA as a disease in its own right.

As with many diseases, gold was also used for RA from the 1920s. Gold salt injections, which only develop an effect after six months, are considered to be the first generation of base medication against RA. The base medications are also called DMARDs (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs). These show anti-inflammatory action and are therefore suitable for long-term administration in patients constantly affected by inflammation.

The year 1948 is considered a key year for rheumatology in the 20th century. In the USA, Philipp S. Hench was the first to use cortisone to treat RA. This approach changed not only rheumatology, but also medicine as a whole, thereby improving the lives of countless patients. Various synthetically produced DMARDs were ultimately approved in the 1950s, such as hydroxychloroquine, which was originally used as an antimalarial agent.

Breakthroughs in the second half of the 20th century

The 1960s and 70s were primarily characterized by new diagnostic developments, which enabled a differentiated classification of various rheumatic diseases. Further milestones in the treatment of RA followed in the 80s and 90s. Among other things, a special highlight was the development of methotrexate. As one of the synthetically produced DMARDs, the medication was adopted quickly and widely in the 80s for its targeted anti-inflammatory effects, ushering in a whole new era of RA treatment.

At the end of the 20th century, the focus was placed on the development of biologic agents. These substances interfere with the inflammatory process, for example by neutralizing proteins that transmit inflammatory signals. Biologic agents include TNF-alpha inhibitors. These drugs are characterized by their outstanding effectiveness – better response rates were achieved in patients than ever before. In the years that followed, there were various new and further developments in the field of biologic agents. These breakthroughs brought with them the hope of slower disease progression or even remission (meaning a symptom-free state defined according to certain criteria) for increasing numbers of patients.

This rapid development has also continued in the last two decades. New modes of action were identified, and corresponding medicines brought onto the market (e.g. anti-IL-6 receptor antibodies and anti-CD20 antibodies in the field of biological agents as well as JAK inhibitors from the group of synthetic basie medications). In addition, new findings allowed the strategy for the use of cortisone medications to be adapted. These continue to play a key role but can now often be administered in smaller doses.1

Thanks to breakthroughs achieved via continuous research and development, a wide range of medicines is now available. This is highly significant since the course of RA differs between patient and the appropriate treatment must therefore be determined individually. Classic pain medications (analgesics), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain relief and anti-inflammatory effects, and cortisone products with a strong anti-inflammatory effect are used for the treatment of RA today. The medications from these groups bring great relief to patients, but have no impact on the course of the disease. DMARDs, on the other hand, do not relieve pain, but have an anti-inflammatory effect in a wide variety of forms (conventional or synthetically produced in a targeted manner or in the form of biological agents).2

However, if RA patients are not optimally treated with medication according to the latest knowledge, they will have a shorter life expectancy, as untreated RA can also spread to organs.3 Thanks to modern RA treatment, however, it has been possible to continuously reduce the number of RA-related deaths:

RA-related deaths among 50–69-year-old women in Switzerland (source: Global Burden of Disease (GBD), https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/#)

RA-related deaths among 70+-year-old women in Switzerland (source: Global Burden of Disease (GBD), https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/#

Precision medicine: fast diagnosis and minimizing the disease burden

The medical breakthroughs of recent years have brought enormous relief for affected patients and massively reduced the disease burden. For example, data from almost 40,000 patients in Germany points to a significant reduction in the mean disease burden. The proportion of those affected with low disease activity rose to almost 50% in the reviewed period. Optimized control of the disease even has an impact on socio-economic factors: at the end of the reviewed period, the number of sick days was almost three times lower than at the beginning.4

It is estimated that about 70% of all RA sufferers could theoretically achieve remission within the first year after diagnosis. In order to achieve this high level, early diagnosis and implementation of the correct treatment are essential.5 The availability of many different medications with differing modes of action allows for treatment adjustment where necessary until the treatment objective is achieved. With a combination of the correct medication and aid measures such as physiotherapy, symptoms can be minimized and the quality of life maintained accordingly.

Precision medicine is likely to provide further advances in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in coming years. Genetic analyses of joint tissue, for example, will make it possible to quickly predict which medications a patient will respond to. Patients will soon no longer be divided into different groups based on clinical parameters to predict the effectiveness of medications. Instead, individual genetic signatures will enable the development of tailored treatment regimens.6 Complications from progressive RA could therefore soon be a thing of the past.

1 Manger B. et al. (2020): 80 Meilensteine der Rheumatologie aus 80 Jahren. I-IV. Z Rheumatol.

2 Rheumaliga Schweiz (2021): Medikamente bei entzündlichem Rheuma.

3 Internisten im Netz (2017): Rheumatoide Arthritis: Prognose & Verlauf. https://www.internisten-im-netz.de/krankheiten/rheumatoide-arthritis/prognose-verlauf/#:~:text=Patienten%20mit%20rheumatoider%20Arthritis%2C%20die,um%203%2D13%20Jahre%20geringer

4 Fiehn, C. (2011): Rheumatoide Arthritis – Meilensteine für Klassifikation und Therapie. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 136: 203–205.

5 Deutsche Rheuma-Liga (2021): Rheumatische Erkrankungen: Zeit ist Remission. https://www.rheuma-liga.de/aktuelles/detailansicht/rheumatische-erkrankungen-zeit-ist-remission#:~:text=Theoretisch%20k%C3%B6nnten%20bis%20zu%2070,der%20Diagnose%20eine%20Remission%20erreichen

6 Northwestern University (2018): Rheumatoid arthritis meets precision medizine https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2018/march/rheumatoid-arthritis-meets-precision-medicine/

First identified in the 1980s, AIDS and the underlying HIV infection developed into a pandemic that has killed an estimated 39 million people to date. Since 1996, when combination drugs were brought to market thanks to pharmaceutical research, the infection has been transformed from fatal to chronic disease, which has enabled them to lead a largely normal life.

Traced back to 100 years ago

The immunodeficiency virus likely first appeared 100 years ago when it jumped from a dead animal to a hunter via a cut and subsequently developed into the human immunodeficiency virus “HIV”. The virus is thought to have spread from Africa to the western world via Haiti in the 1960s. The rapid spread of the virus in the homosexual community ultimately led to the discovery of the disease in the 1970s, which is why it was initially referred to as “gay-related immune deficiency” (GRID). The HI virus mutates so quickly that more different virus variants develop in the body of an HIV-positive person every day than flu variants worldwide. Research into a vaccine, which has been ongoing since the 1980s, has therefore been unsuccessful so far. As a result, the disease is still considered incurable – however, thanks to advances in treatment, HIV is no longer a death sentence.

The development of HIV treatment: various breakthroughs in a very short time

HIV was first clinically observed in the United States in 1981. Since 1984 it is possible to use an antibody test to find out if a person carries the HI virus and it has been mandatory to test blood products for HIV antibodies since 1986. In 1985, the Japanese virologist Hiroaki Mitsuya demonstrated the effectiveness of the substance azidothymidine (AZT), originally developed as a cancer medication, and it was finally approved as the first HIV drug in the USA two years later. This milestone in the treatment of HIV infection made it possible for the first time to counteract the multiplication of HIV in the body and thereby increase the life expectancy of patients. In the late 1980s, it became possible to prescribe two other medications (didanosine and zalcitabine) before they were officially approved. In 1995, the first protease inhibitor was approved in the USA as a novel treatment approach. Eventually, in the mid-1990s, studies showed that combined treatment with two active substances worked better than monotreatment.1

The big breakthrough in HIV treatment came with antiretroviral combination treatment, whereby several drugs are combined. This form of treatment aims to permanently inhibit the multiplication of the HI virus. Combined treatments also remain effective in the long term, since the virus almost never succeeds in simultaneously developing resistance mutations against several medications.

Drug treatment of people with an HIV infection reduces viral load and maintains immune system function. If the viral load of an HIV-positive person can no longer be detected, the treatment is so successful that the patient is no longer infectious.2

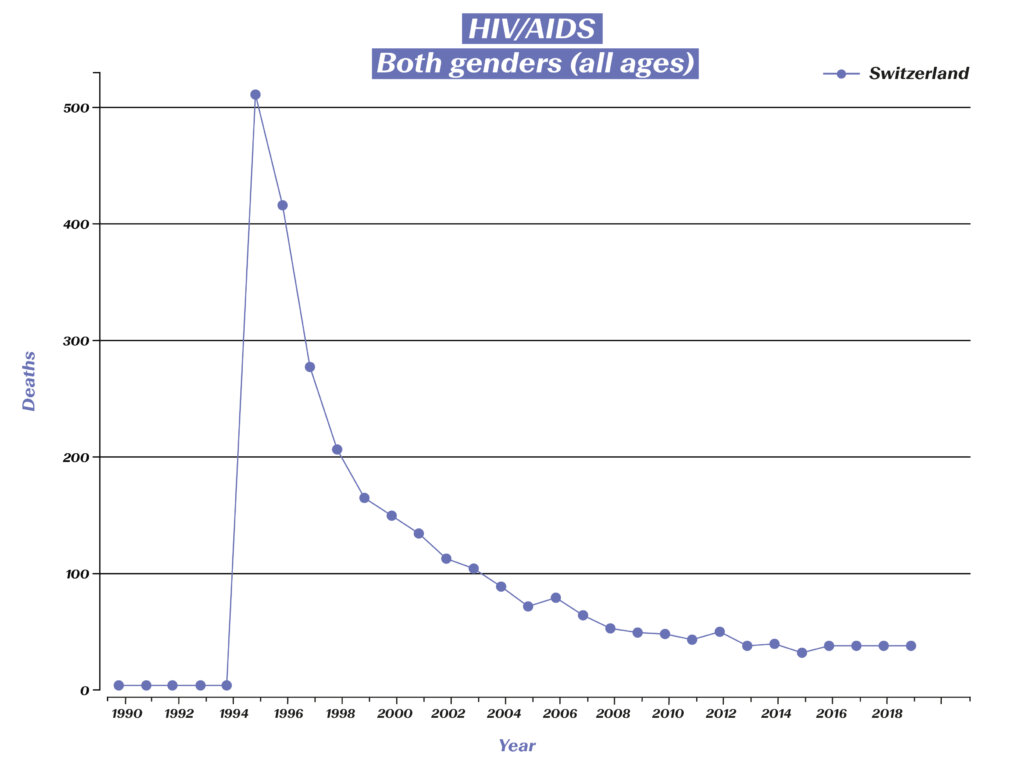

While a positive HIV test still came as a certain death sentence before 1996, in most cases an HIV infection can now be transformed into a chronic disease3. This treatment breakthrough is also underpinned by impressive figures:

Deaths related to HIV/AIDS in Switzerland. (Source: Global Burden of Disease (GBD), https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/#)

While more than 500 HIV-related deaths were recorded in Switzerland in 1995, the number of deaths in recent years has been reduced to around 30. Those affected can live a long life, but this also means that they are dependent on medication for the rest of their lives, as it is impossible to eliminate the virus from the body after infection. Taking the medication as prescribed requires a high level of discipline on the part of the affected individual, therefore research has also made great strides in facilitating the regimen for patients. In the 1990s, a handful of drugs had to be taken at specific and precisely defined times. Now, just one pill a day is often sufficient. Compared to the previous treatment, modern medications also cause fewer side effects in many patients, which also contributes to improving the quality of life of those affected.

Infection prevention, active substances as prophylaxis and a glimpse into the future

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) can now be used to prevent the virus from “implanting” after exposure, so that the exposed person remains HIV-negative. A PEP must be prescribed by a doctor, ideally within 24 hours and no later than 72 hours after exposure. The treatment must be continued for a period of four weeks; the treatment consists of regular HIV medication.

In 2016, a combination treatment in pill form for HIV prevention was approved in Europe. Since then, physicians have been permitted to prescribe the medication as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to healthy adults with an increased risk of infection. Prescribing drugs as PrEP is considered part of an overall strategy to prevent HIV infection, which also includes regular doctor visits and check-ups combined with safer sex practices.

There are currently over 30 medications in eight different medicine classes available to combat HIV. Although we do not have a full cure for HIV infections yet, the example of HIV demonstrates how scientific research can be used to develop treatments and consistently improve them. Hope remains that rapid progress will continue in the coming years and that a cure will soon be found for HIV.

1 Magazin HIV (2011): 30 Jahre HIV – Chronik. https://magazin.hiv/magazin/gesellschaft-kultur/30-jahre-hiv-chronik-1981-1986/

2 Deutsche Aidshilfe (2022): HIV-Behandlung. https://www.aidshilfe.de/hiv-behandlung#:~:text=Bei%20einer%20HIV%2DBehandlung%20werden,die%20Bildung%20von%20Resistenzen%20verhindert

3 Universitätsspital Zürich (2022): Treatment of HIV-infection. https://www.usz.ch/en/clinic/infectiology/offer/treatment-of-hiv-infection/

Rapid progress in diagnostis and treatment options has played a key role in significantly reducing the mortality rate following a heart attack over the past 30 years. Through rapid response and the right medication, many of those affected can now benefit from the medical breakthroughs of the past and significantly reduce the consequences of heart attacks.

Few treatment options until the 1970s

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe unquestionably died of heart disease in 1832: cold sweat, drop in blood pressure with cold limbs, cardiac arrhythmia and finally heart failure and shortness of breath – the classic symptoms. Goethe’s personal physician didn’t understand the cause of this ailment nor had any means of treating it.1 Intensive medical research has completely changed this situation.

Great progress has been made in the diagnosis and treatment of heart attacks, especially over the last few decades. In the 1970s, hardly any effective treatments were available to doctors. In some cases, heparin was already being administered back then, which can prevent further vascular occlusions owing to its blood-thinning effect. After a heart attack, those affected were also prescribed bed rest, often for weeks.1 This is now handled completely differently: Following an uncomplicated heart attack, patients are sometimes allowed to get up on the first or second day and are discharged from the hospital after one to two weeks. This was made possible primarily due to the wide range of medications that are now available for use following a heart attack.2

Major breakthroughs that have become standard

Since the early 1980s acetylsalicylic acid and beta blockers have been administered to patients after a heart attack. The acetylsalicylic acid prevents blood platelets from clumping together and thus the formation of new blood clots. Heparin can also still be used for this purpose. Beta blockers lower blood pressure, slow the heartbeat and relieve strain on the heart. Analgesics and sedatives are often used as well.2

Meanwhile, acute procedures with balloon catheters and stents are also part of the treatment regimen after a heart attack. The era of so-called “percutaneous coronary interventions” began in 1977, when a balloon catheter was used for the first time. The first stents then followed in the late 1980s. The objective of these procedures is to reopen the occluded vessel. The stent serves as a support for the vessel at the narrowed point. Although the introduction of stents was another major advance, in the years following their introduction it became apparent that platelets could easily adhere to their surface, leading to blood clots. For this reason, various medications have been prescribed after stent procedures since the 1990s, usually acetylsalicylic acid mentioned above and clopidogrel (medication to prevent blood platelet aggregation). Today, there are also drug-eluting stents (DES).2

Over the past two decades, thrombolysis has also become an integral part of acute heart attack treatment – in particular when intervention with balloon catheters and stents is not possible.3 Thrombolysis involves an attempt to dissolve the blood clot using administered intravenously drugs with the aim to restore blood flow through the affected vessel.

Rehabilitation after an acute heart attack and handling risk factors

After successful acute treatment, patients are monitored in the intensive care unit for a few more days. If the course is uncomplicated, patients now only stay in the hospital for a few days. Follow-up treatment is carried out in a rehabilitation clinic or in an outpatient setting to facilitate reintegration into everyday life and work. Despite cutting-edge treatment, cardiovascular events may still occur after a heart attack. Drug treatment and close monitoring are therefore of great importance.3 Many of the medications prescribed after a heart attack must be taken permanently. These include beta blockers, acetylsalicylic acid and cholesterol-lowering drugs (statins). ACE inhibitors, which dilate blood vessels and lower blood pressure, are also standard medicines.3

In addition to milestones in the treatment of acute heart attacks, the improved diagnosis of diseases such as high blood pressure or elevated cholesterol levels and the corresponding medication options have also led to progress in combating heart attacks. For example, beta blockers have been used to treat high blood pressure since the mid-1960s and statins have been used to lower cholesterol levels since the late 1980s. Ideally, this treatment would prevent a heart attack from occurring in the first place.4

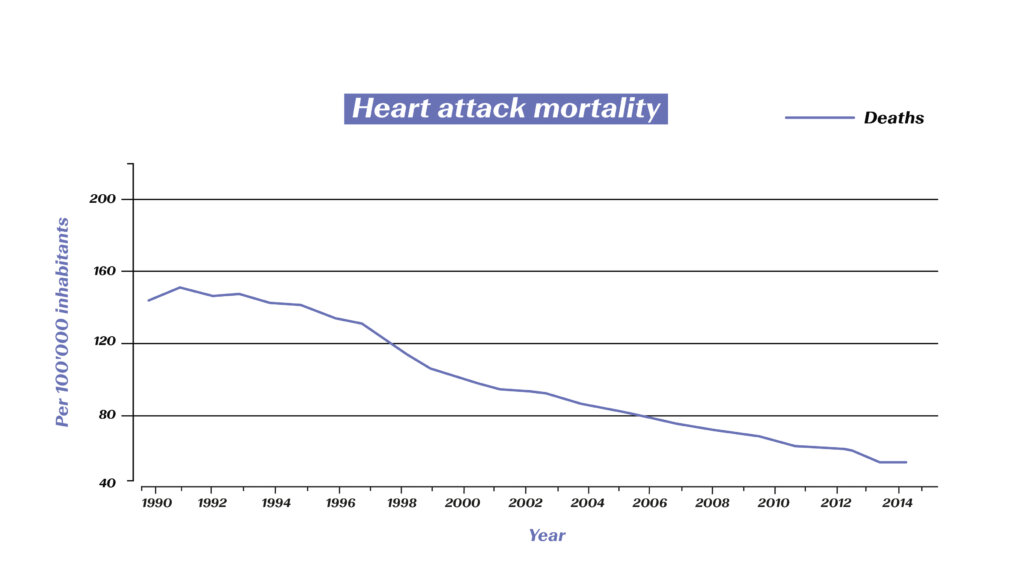

The advances in treatment are underpinned by impressive figures. A recently published study shows a large decrease of the mortality rate in Switzerland for all cardiovascular diseases from 2010 to 2019: over 30 percent for women and over 40 percent for men.4 The greatest advances were made in the treatment of heart attacks. Figures from Germany also underscore this development.

Decrease in mortality from cardiovascular diseases (Source: Meinertz T. et al. (2018). Public Health Forum 26(3): 216-219)

In addition to improved drug treatments, the development of stents and generally improved techniques (e.g. during surgery) have ensured that a heart attack is no longer necessarily a death sentence. Researchers are still working intensively on innovations – both in the prevention and in the treatment of heart attacks and other cardiovascular diseases. Hope remains that treatments such as the recently announced “heart attack injection” will soon become a reality.5

1 Lüscher, T.F. et al (2004): Der Herzinfarkt. Geschichte der kardiovaskulären Medizin. Kardiovaskuläre Medizin 7: 386–391.

2 Deximed (2022): Perkutane Koronarintervention, PCI. https://deximed.de/home/klinische-themen/herz-gefaesse-kreislauf/patienteninformationen/behandlungen/perkutane-koronarintervention

3 Internisten im Netz (2022): Herzinfarkt: Therapie. https://www.internisten-im-netz.de/krankheiten/herzinfarkt/therapie.html

4 SRF (2022): Weniger Tote wegen Herzinfarkt & Co. https://www.srf.ch/wissen/gesundheit/erfreuliche-entwicklung-weniger-tote-wegen-herzinfarkt-co

5 Deutsche Herzstiftung: „Spritze gegen Herzinfarkt“: Wie sieht Kardiologe neuen Cholesterinsenker? – Pressemeldung. https://www.herzstiftung.de/service-und-aktuelles/presse/pressemitteilungen/spritze-herzinfarkt

Breast cancer research has made great strides in recent decades. It has become possible to diagnose cancer more precisely and to treat it in a more targeted manner as it progresses. Thanks to groundbreaking scientific findings, there is now hope for recovery within the framework of primary care for more and more affected people.

Few available treatment options until the 1970s

Descriptions of breast cancer exist from as far back as ancient times, and it was considered incurable for hundreds of years. In the late 19th century it was finally discovered that the removal of the breast, known as a mastectomy, can improve the chances of survival. Removal, in a more or less radical form, was often the only hope for affected women up until the 1970s. Although the operation – now enabling breast conservation in about three quarters of cases – is still an important pillar today, the range of treatment options has been massively expanded in recent decades.

Breast cancer patients have been treated with chemotherapy since the 1980s. The cytostatic agents used have different modes of action and are intended to prevent further division of the cancer cells or even kill them. Radiation therapy also contributes to the combat against breast cancer.

Two breakthroughs lead to a sharp rise in the cure rate

The role of hormones in breast cancer has been a topic of discussion since the early 20th century. The focus has mainly been on estrogen, which was suspected relatively early on to promote the growth of certain types of tumors. A breakthrough, however, was the discovery in 1960 that certain breast cancer cells had hormone receptors. The first medication targeting a hormone finally came to the market in the 1980s. Various types of anti-hormonal treatments are now available. These are incredibly important since around two thirds of all breast cancers are hormone-receptor-positive. The wide availability of this treatment has increased the cure rate by approximately 30%.1

In the 1980s, researchers finally discovered that around a quarter of all breast cancer patients have a very high density of HER2 receptors in the breast cancer cells. It has been demonstrated that these receptors lead to particularly aggressive tumor growth. Based on this groundbreaking discovery, targeted cancer medications were developed for the first time. There are now various anti-HER2 therapeutic agents. Their use in HER2-positive patients has become part of the standard treatment, leading to a large improvement in quality of life. The progression of the disease can be significantly delayed and the survival time extended. 1, 2

Identification of tumor characteristics as a new standard

The described discoveries not only offered new treatment options for patients who previously had little hope of successful treatment, but also laid the foundation for a completely new approach. Identifying the tumor biology characteristics for all patients has now become standard. Not all breast cancer is created equal – treatments can only be effective if the tumor actually has the corresponding structures.3

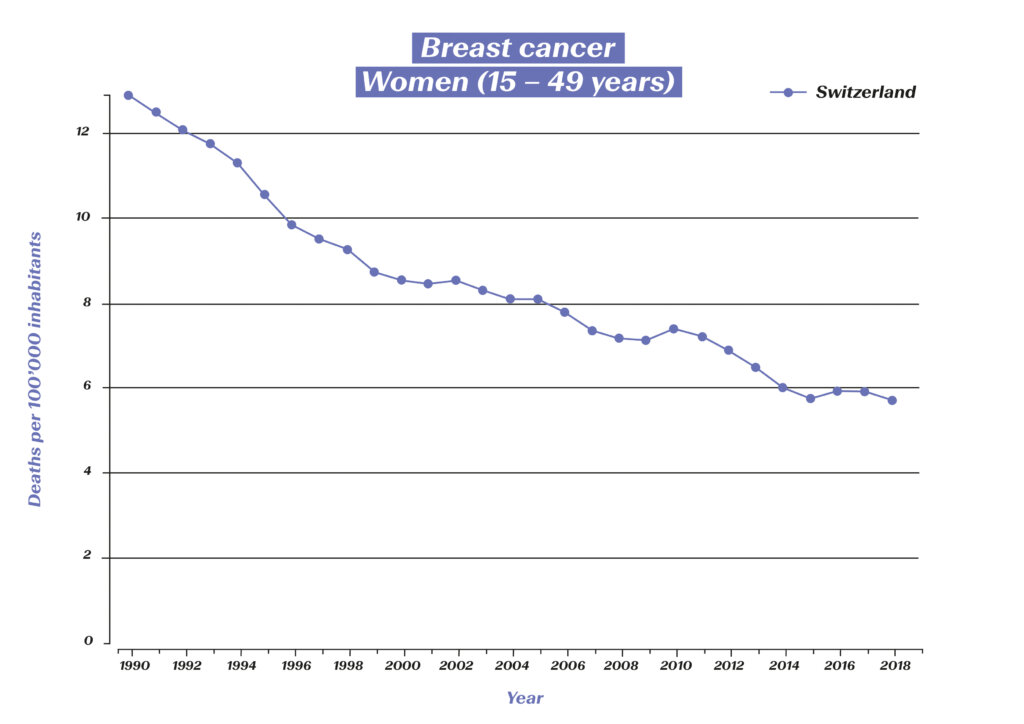

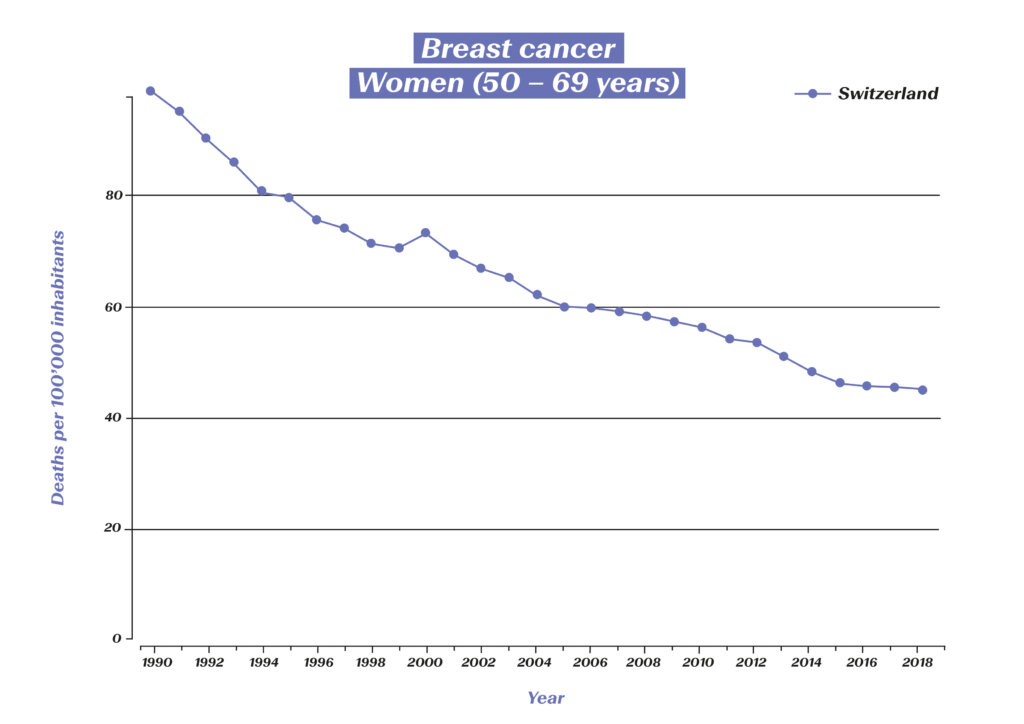

In addition to improved early detection, such milestones in research and development have made it possible to reduce the mortality rate of breast cancer patients by 50 percent over the past three decades:4

Figures 1 and 2: Deaths related to breast cancer among 15–49 and 50–69-year-old women in Switzerland (source: Global Burden of Disease (GBD)), https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/#

Not only has the discovery interval of effective treatment methods for an increasing number of breast cancer types sharply decrease, at sharply decreasing intervals, but it is now also possible to make these new options available to all patients. It is expected that the next few years will bring forth further innovations that will quickly make the leap into primary care. Today, 87 percent of all affected women are still alive five years after diagnosis.5 This proportion will likely continue to increase in the future and additional lives will be saved.

1 Krebsliga (2020): Brustkrebs. https://www.krebsliga.ch/ueber-krebs/krebsarten/brustkrebs

2 Hamburger Ärzteblatt (2012): Das Mammakarzinom im Wandel. https://www.d-k-h.de/fileadmin/Agaplesion_dkh-hamburg/user_upload/121112_Artikel_Brustkrebs_Lindner_.pdf

3 Leitlinien-Programm Onkologie (2021): Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie für die Früherkennung, Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms. https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/032-045OLk_S3_Mammakarzinom_2021-07_1.pdf

4 Bundesamt für Statistik (2021): Schweizerischer Krebsbericht 2021. Stand und Entwicklungen. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/aktuell/neue-veroeffentlichungen.assetdetail.19305696.html

5 Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (2022): Der Erkrankungsverlauf bei Brustkrebs. https://www.krebsgesellschaft.de/onko-internetportal/basis-informationen-krebs/krebsarten/brustkrebs/erkrankungsverlauf.html

The first descriptions of diabetes mellitus, commonly known as the “sugar disease”, is found in ancient records. Up until a hundred years ago, however, there was no effective treatment for those affected, which is why diabetes quickly led to death. Only the discovery of insulin eased the horror of the disease. Since then, pharmaceutical research has produced various improvements that have greatly boosted the quality of life of diabetes patients.

The long road to breakthrough

Although academics were already describing a symptom of “honey-sweet urine” several centuries before Christ, a milestone was not achieved until the mid-19th century, when physicians identified the key role of the pancreas. In the following decades, new discoveries followed in quick succession. In 1916, it became possible to isolate insulin from the tissue of an animal pancreas for the first time. Modern diabetes treatment was born six years later: The process was patented following the first successful treatment, and companies in North America and Europe began producing insulin.1

The further development of insulin therapies

The decades that followed were also shaped by innovation. Between the 1930s and 1950s, medications that enabled delayed insulin delivery were introduced to the market, allowing the number of daily injections to be reduced. In addition, since the 1970s, insulin has been administered to patients in a chromatographically purified form, which has increased tolerability. Since the 1980s, the active ingredient can be produced biotechnologically, which is why no animal-based insulins have been on the market in Switzerland since 2015. This led to a further reduction in incompatibility. To better control insulin therapy, so-called insulin analogues have been developed that better reflect the action curve of insulin produced in the pancreas. Treatment for type 1 patients usually consists of a long-acting basal insulin for primary needs and a short-acting insulin that can be administered as required (e.g. with meals or to correct excessively high blood glucose levels). A wide range of short-, medium- and long-acting insulins are now available.1

Greater quality of life thanks to modern medical products

Not only insulin, but also the associated medical products were further developed during the 20th century. Syringes for self-injection became available just two years after the first successful treatment of a diabetic patient. Insulin pens have been available since the 1980s, replacing syringes and allowing those affected to administer the substance more flexibly, for example when traveling. The first insulin pumps were also developed. These are particularly suitable for type 1 diabetics. The pumps are now not only much smaller, but also have a higher dosage accuracy.

Determining blood sugar levels has also become much easier over time. In addition to blood glucose monitors, various sensors are now available that are attached to the skin and continuously measure blood glucose levels. Furthermore, systems are now available that combine insulin pumps and sensors with electronic controls (e.g. via an app) and act as a kind of “artificial pancreas”. These innovations reduce fluctuations in blood sugar levels, which makes life much easier for patients.2

Stepwise treatment for type 2 diabetes: Alternatives to insulin

In the 1960s, it was found that there are different types of diabetes mellitus. In type 1 diabetes, as described above, the body can no longer produce any insulin – those affected are dependent on insulin treatment.

In the case of type 2 diabetes, however, the body simply does not respond strongly enough to the insulin it produces. Within the framework of what is called “stepwise treatment”, various active substances are now available as treatment options for this form of the disease.

The primary treatment for type 2 diabetes is a lifestyle change consisting of a modified diet and an increase in physical activity. If blood sugar levels do not drop despite these measures, oral antidiabetic agents are used. Metformin, which has been approved in Switzerland since 1960 and increases the sensitivity of the body’s own cells to insulin, is often used as the first-line treatment. The treatment can be supplemented with other medications in a second or third step. The treatment is selected according to the individual requirements of the patient. In addition, sulfonylureas, which stimulate insulin release in the pancreas, have also been used for decades.

If cardiovascular risk factors are present, “SGLT-2 inhibitors” or “GLP-1 receptor antagonists” are now used. SGLT-2 inhibitors promote sugar excretion via the kidneys, while GLP-1 receptor antagonists (glutide) inhibit the release of an insulin antagonist and control meal-related insulin release. These have also been approved in pill form in Switzerland since 2020. before that, they had to be administered using syringes.

Another group of active substances that can be used in the second or third step are the DPP-4 inhibitors (gliptins). These act similarly to the GLP-1 receptor antagonists, but do not show the risk-reducing effects on comorbidities. Glinide (similar effect to sulfonylureas) and glitazones (increase insulin sensitivity of the muscle cells) can also be administered as part of the stepwise treatment, but are less common today than the active substances described above.

Insulin is only used in the third or fourth step if treatment with oral antidiabetic agents alone is not successful. Depending on the patient with type 2 diabetes, it is determined individually whether a short-acting or long-acting insulin is suitable and whether administration should continue in combination with oral antidiabetic agents.3, 4

Since the described medications can be administered orally instead of by injection, taking them requires less effort by the patient. In many cases, it is not even necessary to treat type 2 diabetes with insulin, since the disease can be controlled well with oral antidiabetic agents. Furthermore, during insulin therapy, the sugar is stored in the body as fat deposits, which can lead to weight gain. However, increasing body weight is particularly problematic for patients who are already struggling with excess weight. Oral antidiabetic agents, on the other hand, sometimes even have the opposite effect and can lead to weight loss. The aim of treatment for type 2 diabetes is to push back the disease to a milder stage and – where necessary – to reduce body weight. In many cases, this means that insulin therapy can be avoided.5

The goal of modern diabetes treatment

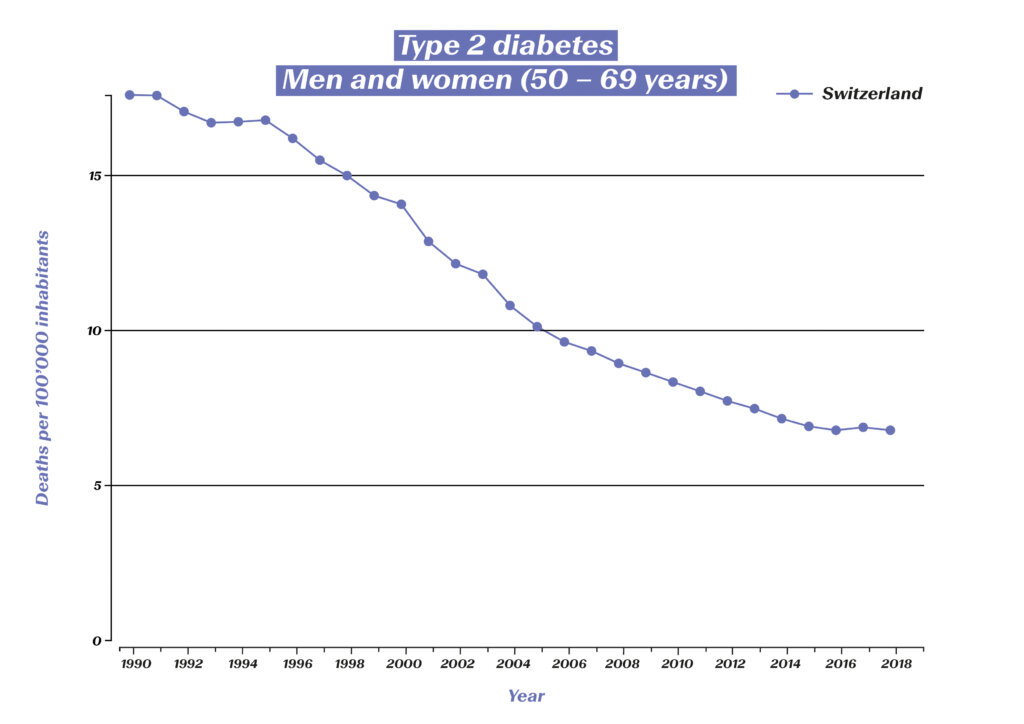

While diabetes still meant a death sentence in most cases at the beginning of the last century, those affected are now able to lead a practically normal life with appropriate treatment. A number of studies show a significant increase in life expectancy for people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. For the periods of 1990–1999 and 2000–2016, a decrease in the mortality rate of people affected by diabetes was observed in 75% of all European countries.6 In Switzerland, too, mortality from diabetes mellitus has been declining since 1990:

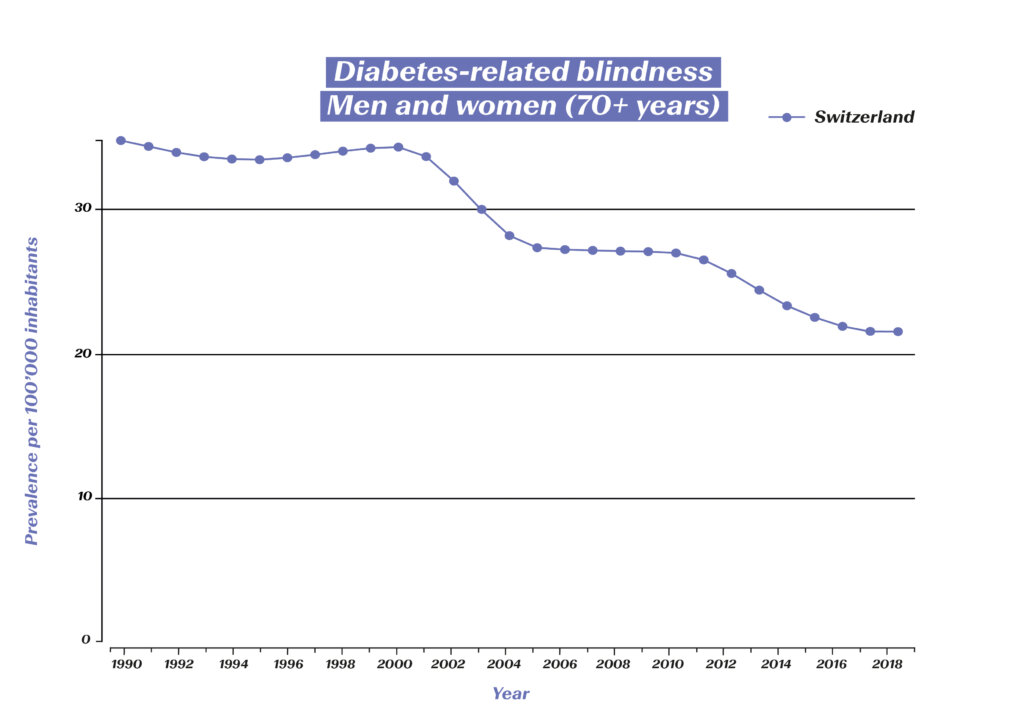

However, the aim of modern diabetes treatment is no longer just the survival of those affected, but also the prevention of consequential diseases (e.g. diabetic retinopathy, diabetic foot syndrome and the associated amputations, kidney failure) and the optimization of quality of life. There are also figures to show how well this is now being achieved: The incidence of amputations in diabetes patients has fallen significantly. Figures from eleven OECD countries show a decline of almost 30% between 2000 and 2013.7 The blindness rate has also been massively reduced in the past 30 years:

Diabetes-related blindness among 50–69-year-olds in Switzerland (source: Global Burden of Disease (GBD)), https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/#

Diabetes-related blindness among 70+-year-olds in Switzerland (source: Global Burden of Disease (GBD)), https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/#

It is foreseeable that research will continue to generate further innovations in the coming years that will give people with diabetes even greater flexibility. What is known as “precision medicine” will play a key role here. Thanks in part to artificial intelligence methods, it is already becoming increasingly possible to identify and treat subtypes of diabetes as well as the associated risks and complications.

1 Österreichisches Diabetes-Museum: Die Geschichte der (modernen) Diabetes-Behandlung. https://diabetes-museum.at/geschichte-diabetesbehandlung

2 Deutsche Diabetes-Hilfe (2022): 100 Jahre Insulin: Die Geschichte des lebenswichtigen Hormons. diabetesde.org/100-jahre-insulin-geschichte-lebenswichtigen-hormons

3 Mehnert, Hellmut (2019): Orale Antidiabetika: Ab wann? Welche? Wie lange? Ars Medici 21: 721-723.

4 Universitätsspital Zürich (2022): Diabetes mellitus – Behandlung. https://www.usz.ch/fachbereich/endokrinologie/angebot/diabetes-mellitus/#typ-2-diabetes

5 Diabinfo (2021): Diabetes Typ 2: Medikamente. https://www.diabinfo.de/leben/typ-2-diabetes/behandlung/medikamente.html

6 Kulzer, B. (2022): Körperliche und psychische Folgeerkrankungen bei Diabetes mellitus. Bundesgesundheitsblatt 2022 (65): 503–510.

7 Carinci et al. (2020): An in‑depth assessment of diabetes‑related lower extremity amputation rates 2000–2013 delivered by twenty‑one countries for the data collection 2015 of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Acta Diabetologica 57(3): 347-357.